TL;DR; If you like the humour of Monty Python, you’ll really enjoy this book. If, however, you are looking for a book about Monty Python, you’ll be disappointed. This is Eric Idle’s story, which wouldn’t be complete without Monty Python, but it is also much more than that. I came across this book by accident and what a happy accident it was.

The story of this book and my relationship with it would be incomplete without “the tweet”.

Yes, Eric Idle called me a cunt.

I’m still not quite sure why. I mean, I am merrily reading along and he’s talking about his retreat in Provence. By this point in the book his fame has caused his orbit to cross paths with pretty much everyone who was anyone at the time, and he’s managed to make friends with a lot of famous people. He’s writing about his eccentric neighbor with a wheelbarrow that uses a ball instead of a wheel (ballbarrow?) who turns out to be James Dyson.

Of course he is.

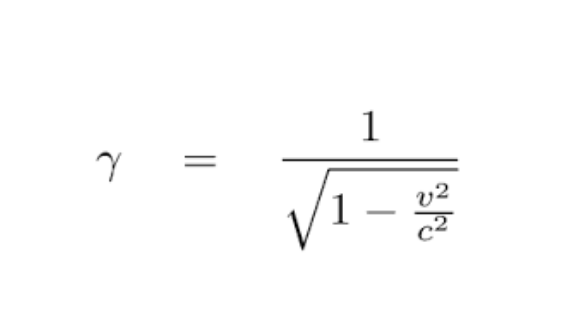

So, as part mental exercise and part futile effort to show my friends how clever I am, I decide to guess a famous person one wouldn’t usually associate with Monty Python that Idle will inevitably meet. I chose Stephen Hawking (who, by the way, shows up on page 238).

I didn’t think much of it and went to bed, and when I woke up I saw his reply. In a way it was kind of funny. I imagine Idle at his home in LA, feeling a little lazy after having eaten dinner, pulling out his phone and taking offense, but that sneaky autocomplete jumped in and turned “cunt” to “count”.

Idle is English, so technically one would be an Earl and not a count, but for some reason the wife of an Earl is still a Countess, go figure. I decided to have some fun with it, so for the next 31 days I will be known as “Count Balog”, complete with the Eastern European pastiche accent (à la the character on Sesame Street). My tweets autodelete when they are 31 days old so this too shall pass.

I came across this book entirely by accident. Where I live in North Carolina we have seen an obscene amount of rain this year, nearly double the average, including two hurricanes. Hurricane Florence damaged the Biography section of the Wren Memorial Library in Siler City, and they asked for help replacing the damaged books through an Amazon wishlist. Near the top of that list was this book.

Now Siler City has seen better times, and it is best known for being the final home of Frances Bavier, Aunt Bee from The Andy Griffith Show (after she died Andrea was involved in rescuing the cats she left behind, but that’s another story). It is also home to a bunch of hard working people who have been duped into voting against their own self interest. I found it a moral imperative to replace this book, even though I had not read it, because I knew the viewpoints expressed would be counter to, say, Fox News. I bought it and sent out a tweet, and Eric Idle was kind enough to comment on it (without elevating me to royalty) and I believe that caused a few more people to contribute. I am grateful for that.

About a month later I found myself at Flyleaf Books, which is my favorite local independent bookstore, when I saw a copy of Always Look on the Bright Side of Life. I bought it and put it in the queue of things to read.

Now I have been a Python fan since the late seventies. I can’t remember who introduced me to their work, but I believe it started when the DM for the Dungeons and Dragons group I was in started talking in a Pepperpot voice as one of his characters (yes, I liked Monty Python and D&D in the South. Oh how the young ladies flocked to me). We devoured all things Python and Python adjacent. When cable television arrived I recorded The Rutles onto VHS and wore the tape out. We made cassette copies of all the albums, having to struggle a bit with the second side of Matching Tie and Handkerchief to get both sides recorded. In high school, when my friend David and I were cutting up in social studies class, the teacher Jackye Meadows called us on it so we immediately launched into singing “Sit on My Face”. She didn’t know what to think of it, but being very cool she let us slide.

Well, enough foreplay, let’s talk about the book.

Billed as a “sortabiography” the book begins and ends with a song, namely “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” which was the closing tune of The Life of Brian. I can remember seeing the movie in the theatre, and the song gave me an earworm for weeks. Monty Python was known for not finishing things. Skits would abruptly end, and even Monty Python and the Holy Grail just ends with everyone getting arrested. It was surprising to actually have some sort of ending to a Python movie, and a rather good one at that. This song is the thread that holds the book together.

There are several arcs within this book. Like any autobiography it starts when the author is young and, in this case, comes pretty close to present day by the end. One arc involves Monty Python, of course. One follows the numerous friendships he made over the years and their impact on his life, and still another follows his relationship to his family. The three combine to show how Idle grew as both a person and an entertainer over decades.

Idle’s childhood was far from idyllic, but he managed to cope. I really identified with his story about leaving boarding school to see movies in town by simply walking out the front door like he had every right. It’s how I find clean toilets in Europe. I pick the fanciest hotel nearby and walk in like I own the place. I’ve never been stopped or even questioned, and often someone will even hold the door to the hotel open for you.

In trying to understand why my tweet pissed him off, I read some reviews. The second most critical comment is that the book doesn’t contain enough Python. Well, right there on page 39, at the start of Chapter 7, is a whole paragraph about how so much stuff has already been written about Monty Python. What more needs to be said? This book is more about how Python played a role in Idle’s life versus a history of that show. And what it did was make him a celebrity.

The number one complaint, and I believe the source of his ire toward me, is that he mentions a lot of celebrity names. Apparently it bothered some people. It didn’t really bother me, because, seriously, who do celebrities hang out with outside of other celebrities? They are the only ones who can understand how celebrity affects one’s life, regardless of if it comes from music, acting, art, or even comedy. I found the rapid-fire stories of meeting famous people, ingesting various substances, jetting off to amazing places and shagging models kind of gave me a glimpse of what his life must have been like, especially in his younger days.

I couldn’t help but think as he was talking about all the temptations he yielded to, which often involved intimacy with beautiful young women, “What about his wife? Isn’t he married at this point?”

He soon addressed that. His son Carey was born in 1973 just before Grail and before The Rutles. In a chapter entitled “The Divorce Fairy” he owns up that his marriage to Lyn was ending just as 1976 was arriving and that it was primarily his fault. While he never really alludes to his current relationship with her, he does obviously care for his son who remains a fixture throughout the book. By the next chapter his talks about “growing up” at age 33 and meeting his second (and current) wife Tania. From what I read in the book Tania’s only flaw seems to be poor taste in men (much like my wife Andrea) and she even likes German Shepards.

Things seem to settle down a bit after he meets Tania. Sure, there are still stories of hanging out with celebrities but we also start to see him develop as a performer. While the Monty Python television series was long over, the troupe found new life in movies. He talks about the Python movies Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life as well as his very funny yet underrated Nuns on the Run (hurray for cable television in the South).

One of my favorite parts of the book is when he talks about the uproar over Life of Brian being sacrilegious. I can’t do it justice, so here is the quote:

We agreed early on, you couldn’t knock Christ. How can you attack a man who professes peace to all people, speaks out for the meek, heals the poor and cures the sick? You can’t. Comedy’s business is some kind of search for the truth. Clearly this was a very great man, leaving aside for a minute his potential divinity. No, the problem with Christianity was the followers, who would happily put each other to death at the drop of a dogma.

After The Meaning of Life and the death of Graham Chapman, Idle gets involved with stage plays and musical theatre. This eventually results in the mega-hit Spamlot which won the Tony for best Musical in 2005. Toward the end of the book there are stories about the famous Monty Python Live (Mostly) show at O2 arena. I watched a recording of this show and was pretty amazed at the rather lavish and professional production that included huge musical numbers complete with chorus lines, etc. It didn’t surprised me that Idle was the driving force behind it. After all, it is what he had been training for for years.

It was also then that I remembered the gag at the end of the “Galaxy Song” involving Stephen Hawking, so maybe I cheated, albeit subconsciously, in my guess that they would eventually meet.

I also enjoyed the stories of his friendships, especially with George Harrison and Robin Williams. I was horrified when I read his description of the attack on the Harrison home by a mentally deranged man, and I shed several tears reading about George Harrison’s death. I didn’t know that it was George Harrison who provided the financing for Brian, mortgaging his home to do it, simply because he believed in them and wanted to see the movie.

I also got a little verklempt reading about Robin William’s suicide. Of all the recent celebrity deaths, that one bothered me the most. Robin was kind of a geek idol: someone who showed it was okay to be weird, to be funny. I adored that man, although I never met him.

I remember two things about his death. On the news that night they led with his story, but later in the broadcast they mentioned that Kim Kardashian had produced a book of selfies that had immediately sold out. Now I have nothing against Ms. Kardashian making a buck, but I thought it was sad to live in a world where Robin was dead and selfies were trying to take his place.

That night I had a very realistic dream that I was able to stop him from committing suicide. For some reason I ended up at his house, and when he came to the door I could tell something was wrong. We talked for hours and when I finally left he was feeling better. We know now from the autopsy that his depression was caused by Lewy body dementia so no amount of talking would have helped, but it was a nice dream in any case.

The book ends with stories about a tour Idle did with John Cleese. I remember reading an interview with Cleese about that tour where a woman in Florida asked, in all seriousness, “Did the Queen kill Princess Diana”.

Cleese replied, “Certainly not with her hands”.

Although I can’t find an authoritative reference, Thoreau is credited with saying “Most men lead lives of quiet desperation, and go to their grave with the song still in them”. This is definitely not the case with Eric Idle. He is still living an amazing life and, it is hoped, still singing.